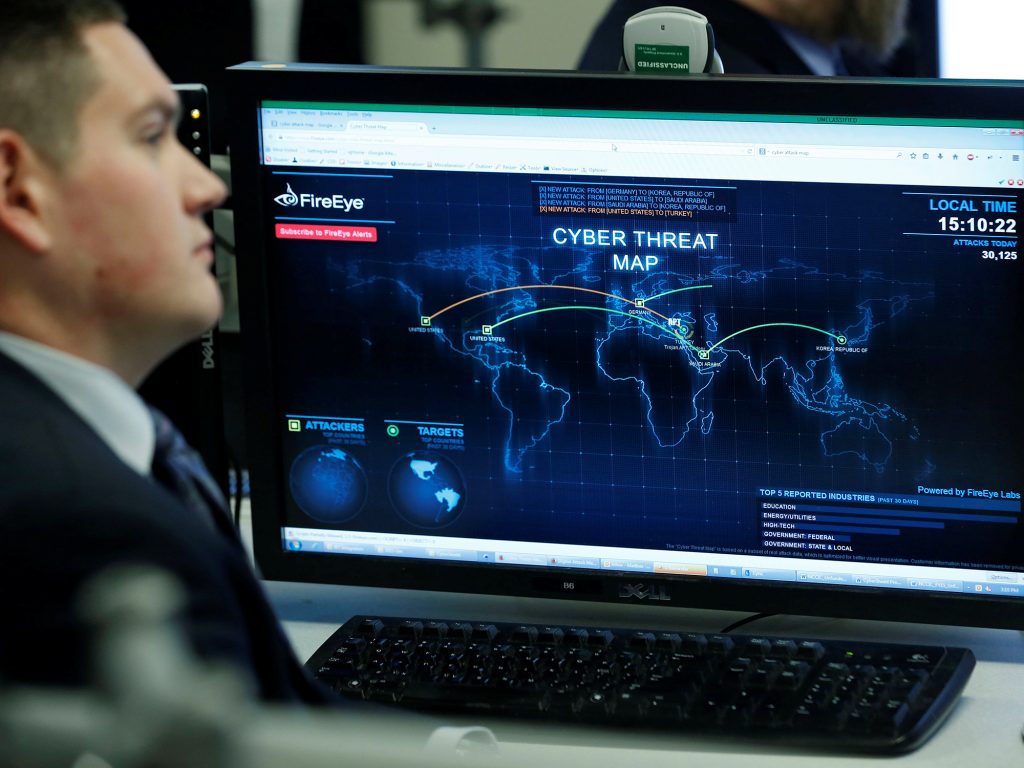

A Department of Homeland Security worker listens to US President Barack Obama talk at the National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center in Arlington, Virginia, January 13, 2015. (REUTERS/Larry Downing/File Photo)

Many in the defense community have still not embraced hacking as a combat mission or the work of securing systems and networks transitioning from administrative job into warfighting function. This transformation has led to much theorization and debate, yet as a practical matter remains poorly understood at the policy level. This is partly is due to linguistic limitations; the difficulty of agreeing what to name new concepts, and how to adopt a universal verbiage to describe conflict between humans for centuries. More substantively, fighting over the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of digital devices and services occurs in ways that are not easily observed by those who are not immediately “at the front” with access to network logs and digital artifacts. Persuasive arguments that offensive cyber capabilities are the first military innovation developed directly from the intelligence community imply that cyber operations continue to follow—as Jon R. Lindsay puts it—“logic of intelligence.” But intelligence as an organization and an activity is often overwhelmingly secretive, and so too are cyber operations.

USCYBERCOM’s decision to declassify a series of foundational

documents related to one of its most prominent cyber operations is therefore a

unique opportunity to draw back this veil. The

National Security Archive at George Washington University has done a

tremendous service to international relations, intelligence studies, and

defense scholars in pursuing and assembling these materials. Critically, the

Archives work occurred under proper review processes—in a manner that preserves

key intelligence and operational equities—while offering a unique view into

Joint Task Force Ares (JTF Ares) and Operation Glowing Symphony. This view is

by necessity incomplete, but it is a better picture than passing comments about

dropping “cyber

bombs,” or stolen glimpses otherwise offered by unauthorized leaks and pilfered

documents. It presents a record clean of the problematic manipulation of

ideologically motivated defectors, shadowy third parties, and the machinations

of hostile intelligence services.

This Cyber Vault collection

illustrates aspects of contemporary offensive cyber operations that have been

understudied and too little recognized. First among them is the fundamentally

corporate nature of the effort. This is not the hacking of cinema, a lone

genius clad in a hoodie and toiling in the dark of night—or at least a darkened

basement. Instead, the documents portray the mobilization of a bureaucracy akin

to Ford Motors, rather than Nikola Tesla. While this is almost certainly not

the first mobilization of its kind, to date JTF ARES is perhaps the clearest

outline of the enterprise. The organization is a true multiservice contribution:

an assembling of key capabilities into a coherent form directed by the

combatant command for specific purposes. It speaks to years of investment to

man, train, and equip the forces outlined in the Task Order, who are now employed

to combat a violent extremist organization that threatens the United States and

its allies.

The materials also outline the continuing nature of that

investment: the need to develop and sustain specific offensive capabilities to

assure access and deliver effects against adversary targets in unpredicted or

future circumstances. This sustaining development is only lightly touched upon,

but it must

balance against the complex calculus of vulnerabilities, equities, and the

probability of detection. Questions of national policy embedded in managing

an arsenal of cyber capabilities have

been the subject of debate in recent years. The arsenal

management dilemma is made even more prominent in the face of what may

potentially be a depletion of stockpiles at a more rapid rate than one might

otherwise expect in the course of ongoing operations, as opposed to the routine

lifecycle of bug discovery, patching, code churn, independent re-discovery and tooling detection

that normally dictates the longevity of a given capability.

There is no mistaking: this is combat between organizations.

The Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) is a product of utterly modern

global communications networks welded to an ideologically twisted variant of a medieval

governance model. The systematic nature of the group’s activities in cyberspace

comes through clearly in the Operation Glowing Symphony (OGS) declassified concept

of operations (CONOPS) and associated briefings. These are functions essential

to ISIS’s survival as an organization—internal communications, foreign fighter

recruitment, fanatic lone wolves, and the promotion of its global brand for

fundraising and material support. The documents make notable reference to the

underexplored role of ISIS cadres in acquiring and administering the group’s

technology infrastructure, as well as brief mention of the group’s aspirational

cyber espionage and attack capabilities. These ISIS members would naturally be

a target for operations intended to disrupt and degrade key terrorist

activities.

The distribution of the ISIS’s online presence also

illustrates the importance of global relationships in contemporary cyber

conflict. No fight can be pursued without support from allies and partners—particularly

when targets cut across traditionally segmented law enforcement or diplomatic

instruments. While coalition members may approach operations in different ways,

it is apparent that these relationships—including processes for notification

and coordination—are featured prominently in these operations.

This strongly contradicts public stereotypes of unilateral “cowboy”

military cyber operations, a fact pattern further reinforced by the

declassified document collection. OGS appears to be characterized by a

remarkable degree of restraint; closely managed processes for targeting, delivery

of fires, and assessing effects are outlined. These processes include formal

mission planning within specific constraints, operational law review,

intelligence gain/loss evaluations, political and military assessments,

blowback assessments, rehearsal, mission reporting requirements, and lessons-learned

activities.

The Archive has done itself a great credit in securing the

release and managing the curation of these documents which help show, to a

previously unreported degree, the complexity in design and executing offensive

cyber operations which help distinguish an ‘American way’ of cyber warfare—one

that is no doubt closely mirrored by many of our allies. Indeed, this model of

cyber warfare could be a model the development of future norms. Restraint and

sober consideration ought to be expected of any actor who engages in

intelligence or effects actions in the networked environment.

JD Work is an intelligence professional and educator,

currently serving as the Bren Chair for Cyber Conflict & Security at the

Marine Corps University, Krulak Center. He additionally holds affiliations with

Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, Saltzman

Institute of War and Peace Studies as well as George Washington University,

Elliot School of International Affairs. He further serves as a senior advisor

to the US Cyberspace Solarium Commission.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the

author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any

agency of the US government or other organization.

Further reading

Wed, May 22, 2019

Did the IDF’s airstrike ‘cross the Rubicon’ by using lethal force in response to hacking? On the weekend of May 5, a month after a truce was agreed between Israel and Hamas forces in the Gaza Strip, violence again rose to levels not seen since 2014.

New Atlanticist

by

Jack Watson and William Loomis

Wed, Apr 24, 2019

The need to update the cybersecurity model is clear. An enhanced public-private model – based on coordinated, advanced protection and resilience – is necessary to protect key critical infrastructure sectors

Report

by

Franklin D. Kramer and Robert J. Butler

Tue, Apr 23, 2019

Shifting tactics have prompted federal authorities to change their approach to defense, Krebs says.

New Atlanticist

by

David A. Wemer

The Cyber Vault collection shows the complexity in design and executing offensive cyber operations which help distinguish an ‘American way’ of cyber warfare—one that is no doubt closely mirrored by many of our allies.

|