Gateway to Think Tanks

| 来源类型 | REPORT |

| 规范类型 | 报告 |

| Innovation in Accountability | |

| Samantha Batel; Scott Sargrad; Laura Jimenez | |

| 发表日期 | 2016-12-08 |

| 出版年 | 2016 |

| 语种 | 英语 |

| 概述 | The Every Student Succeeds Act gives states the opportunity to broaden their vision of accountability and create school classification systems using new measures of school quality or student success. |

| 摘要 | Introduction and summarySchool accountability in the United States is evolving—and for good reason. Rather than merely labelling failure, accountability should provide information on school progress and inspire a culture of continuous improvement. To accomplish this goal, the concept of accountability must become much broader so that it encompasses a system of data collection and reporting, classification of school performance, direction of supports and implementation of interventions, and assessment of resource allocation. The Every Student Succeeds Act, or ESSA, is a key lever for this broader vision. The new law requires states and districts to create comprehensive data dashboards; states to design systems that identify schools for improvement using new measures of school quality or student success; and districts to develop improvement plans based on school-level needs assessments. To support this broader vision, states and districts should also use their systems to direct resources to schools that are not identified for improvement but need additional supports. Although just one component of the greater accountability system, school classification systems are a top priority for states.1 As states design these systems, much of their attention is focused on which indicators of school quality or student success they will use for a more holistic measure of school performance.2 According to ESSA, these new indicators may measure one or more of the following:3

This approach is an important shift from previous iterations of federal law, which often focused on a single test on a single day. The Improving America’s Schools Act—the 1994 reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, or ESEA—cemented accountability as a strictly academic notion.4 The No Child Left Behind Act, or NCLB—the 2001 reauthorization of ESEA—strengthened this premise and required districts and schools that failed to make academic progress to take specific improvement actions.5 NCLB also required states to hold schools accountable for an academic indicator other than student achievement in reading and math. However, states viewed this as simply another way to potentially miss their yearly targets instead of an opportunity for improvement. As a result, states largely limited measures to graduation rates for high schools and, most commonly, attendance for elementary and middle schools. Some states also began to measure student growth in academic achievement. The Obama administration’s 2011 waivers from particular NCLB provisions, known as ESEA flexibility, marked the beginning of a departure from this limited focus.6 By 2015, the U.S. Department of Education had approved 42 states and the District of Columbia for ESEA flexibility, giving them the opportunity to expand accountability measures beyond test scores and graduation rates. Fourteen states with ESEA flexibility, for example, added measures of persistence to their accountability systems, such as the dropout rate. Thirty states incorporated measures of college and career readiness, including performance on advanced coursework exams, the percentage of students earning career readiness certificates, and postsecondary enrollment. In addition, 27 states included other indicators that were either unique to their state, reflected state values, or were designed to incentivize particular school activities.7 As the latest reauthorization of ESEA, ESSA builds on this progress by carving out space for new measures of success while maintaining an emphasis on academic outcomes. In doing so, the law recognizes that test scores do not tell the whole story and shines a spotlight on additional indicators of student performance. Many states already use an indicator of college and career readiness at the high school level, and these measures are good candidates for indicators under ESSA. This report explores some newer, less commonly used indicators, including measures of social and emotional learning; school climate and culture; and resource equity, which have recently caught the attention of state policymakers. Few states—if any at all—currently use a measure of social and emotional learning, school climate and culture, or resource equity to classify schools. For example, only four states include a measure of school climate and culture, such as a climate survey, in their school classification systems. Five states include chronic absenteeism, which can be a useful proxy for a school’s climate, and one state pays particular attention to student and parent engagement. Five states use some measure of resource equity, such as student participation in the arts. And no state uses a measure of social and emotional learning to classify schools.8 A group of districts, however, offers insight for states considering some of these new indicators. The California Office to Reform Education, or CORE, districts created a school classification index that includes both social and emotional learning and school climate and culture indicators. This report examines lessons learned from this work. As states consider these new indicators, they must keep in mind that school classification systems are only one part of a broader vision of accountability. To support continuous improvement, accountability systems should also include indicators that are appropriate to examine at the district or state level, such as measures of resource equity. This report highlights measures of student access to highly effective teachers, access to early learning opportunities, school funding, high-quality curriculum, a well-rounded education, and student health and wellness. As states take on this work, the Center for American Progress recommends the following:

States should take the opportunity provided under ESSA to design comprehensive systems of accountability that use multiple indicators to support continuous improvement. Under this broader vision, states should use some indicators to classify schools; others to inform local decisions about resources and supports; and all measures to ultimately support classroom teaching and learning, school quality, and student success. CORE School Quality Improvement IndexIn 2013, a group of districts in California, known as the California Office to Reform Education, received approval from the U.S. Department of Education to design a district-level school classification system separate from the statewide system. CORE’s index consists of two domains: an academic domain and a social-emotional and culture-climate domain.9 Academic domain

Social-emotional and culture-climate domain

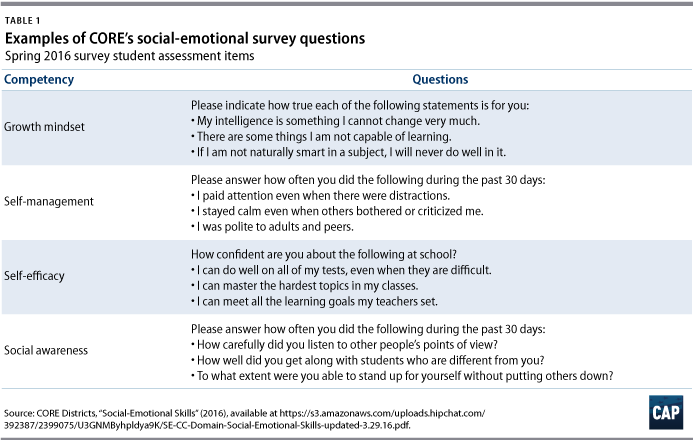

In 2016, CORE requested that California establish the districts as a research pilot so that it may use its system, instead of the statewide school classification system, in order to identify low-performing schools under ESSA.10 This innovation will have important implications, as the state may decide to scale up measures that the districts determine to be particularly useful. Indeed, California is already considering CORE’s culture-climate surveys as an option to assess school climate in its school classification system.11 If approved, the districts will classify schools using the following index. (see Figure 1)  In the meantime, CORE is collaborating with several organizations to learn which of its districts use these data well, particularly in the social-emotional and culture-climate domain, and how schools apply this information to improve teaching and learning. Ideally, CORE would like to develop multiple options to measure students’ social-emotional skills, such as performance-based assessments.12 Social and emotional learningStudents’ intelligence alone does not determine their academic success. Other skills matter greatly, and which skills particularly contribute to performance has increasingly become the focus of education research. Attributes referred to by a plethora of terms—including but not limited to noncognitive skills, soft skills, 21st century skills, and personal qualities—can have substantial effects on student achievement.13 This report use the term social and emotional learning, or SEL, to refer to these traits. The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, or CASEL, defines the goals of SEL as the development of five competencies:

Together, these competencies address students’ ability to recognize and regulate their emotions and behaviors, empathize across differences, maintain healthy relationships, and make respectful choices in social interactions.14 Social and emotional learning correlates with positive student outcomesThe famous marshmallow test—a classic example of delayed gratification—illustrates the power of the social and emotional skills that CASEL outlines. Psychologists found that preschoolers who were able to delay eating one marshmallow in order to receive two marshmallows were more likely to score higher on the SAT as adolescents. The children’s parents were also more likely to rate their child as better able to handle stress and exhibit self-control in high school. Impressively, these results held up for decades. The researchers found that subjects’ willpower strength in their 40s correlated with their self-control at the age of four.15 Honing these competencies, accordingly, can have transformative effects. Indeed, quality SEL programs have been shown to improve academic performance, reduce disruptive behavior and emotional distress, and decrease the likelihood of receiving public assistance. SEL interventions also yield, on average, $11 for every $1 invested.16 For example, a meta-analysis of school-based and afterschool SEL programs found that participation improved elementary and middle school students’ test scores by an average of 11 to 17 percentile points, decreased conduct problems, and increased students’ problem-solving skills.17 Similarly, a meta-analysis of school-based SEL programs for students in kindergarten through 12th grade found that participation improved students’ academic performance by 11 percentile points, reduced their anxiety and stress, and increased their prosocial behavior.18 These programs were successful in all geographic locations, including urban, suburban, and rural school environments.19 Developing SEL standardsIn 2003, Illinois became the first state to adopt comprehensive preschool to high school SEL standards, which use grade span benchmarks to create learning targets. For example, early elementary school students in Illinois should be able to understand how emotions relate to behavior and demonstrate impulse control. By late high school, students should be able to evaluate how expressing more positive attitudes affects others.20 In 2007, Illinois funded a cohort of schools to implement the state’s SEL standards during a three-year period. The pilot project found that fidelity to the standards paid off. Not only did teachers notice a positive change in student behavior, but compared with schools that were not making adequate yearly academic progress under NCLB, schools that were meeting their annual academic targets also had a greater commitment to SEL.21 According to the most recent CASEL analysis, there is increasing momentum to bring SEL into the classroom.22 In addition to Illinois, Kansas and West Virginia also have in place freestanding, or independent, comprehensive SEL standards with developmental benchmarks for preschool through 12th grade.23 Another eight states have developed freestanding SEL standards for some grade levels, most of which target kindergarten and early elementary school, and all 50 states have SEL standards at the preschool level.24 As of July 2016, eight states—two of which already have some standards in place—are collaborating with CASEL to develop new SEL standards and policies. This partnership was inspired, in part, by CASEL’s earlier collaboration with eight mostly urban school districts.25 A 2014 evaluation of this work concluded that districts successfully implemented SEL standards and programs with high levels of fidelity in their large school systems. And schools with higher levels of implementation decreased discipline rates, improved attendance, and, in many cases, improved academic performance.26 One priority of CASEL’s eight-district collaboration was to align and integrate SEL practices and standards with other district initiatives and standards. For example, nearly all of the districts that successfully aligned SEL standards began to integrate them with the Common Core State Standards.27 The Common Core also contains its own SEL-related standards, such as communication, cooperation skills, and problem-solving.28 Additional SEL opportunities include curriculum such as Tools of the Mind and Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies, or PATHS, which have been shown to improve student achievement, decrease conduct problems, and improve mental health.29 And, in 2015, the U.S. Department of Education announced the Skills for Success grant competition to integrate SEL skills into the classroom and the Mentoring Mindsets Initiative partnership to prepare mentors to teach students learning mindsets and skills.30 Measuring SELAlthough CASEL and states across the country have considered social and emotional competencies, standards, and curricula, there are no commonly defined measures of SEL. California’s CORE districts have taken this work a step further as the first policymakers to design SEL measures to include in their school classification system. To create these metrics, the CORE districts prioritized skills that are predictive of important student outcomes, can be reliably measured, and are actionable for schools.31 Based on these priorities, the districts developed survey questions to identify four main competencies, including growth mindset, or students’ belief that their ability can grow with effort; self-efficacy, or the belief in the ability to reach a goal; self-management, or the ability to regulate one’s emotions; and social awareness, which includes the ability to empathize.32 In spring 2014, CORE conducted a pilot test of its SEL measures with approximately 9,000 students and more than 300 teachers from all grade levels.33 The districts found that on average, students’ self-reported survey responses on all four competencies were correlated with GPA and standardized test scores in English language arts and mathematics. Furthermore, teacher reports on students’ social-emotional skills, in combination with student self-reports, were more highly correlated with these academic measures than were student reports alone. However, due to cost and capacity, CORE decided that teacher reports would be optional going forward.34  In spring 2015, CORE conducted a systemwide field test of its social-emotional measures with more than 450,000 students from the six participating CORE districts and more than 2,700 teachers from two participating CORE districts. Both student self-reports and teacher reports were found to be significantly predictive of student academic and behavioral outcomes, including GPA, state test scores, suspension rates, and absenteeism. Furthermore, the four individual skills were separately more predictive of student outcomes compared with a composite social-emotional measure. Accordingly, in the 2016-17 school year, CORE will include on its school report cards information on each measure: growth mindset, self-efficacy, self-management, and social awareness.35 Concerns about measuring SELRecent research suggests that questionnaires such as CORE’s are the primary tools in development to measure students’ social-emotional skills.36 As SEL gains popularity in the classroom, however, there is increasing concern about the potential unintended consequences of using survey data to hold schools accountable for these competencies. One main concern is reference bias, or the effect of survey respondents’ reference points on their answers.37 Students, for example, attending competitive schools often rate themselves as having less self-control or as less hardworking because of their schools’ rigorous expectations.38 Accordingly, some experts caution that using SEL to classify schools could ultimately punish high-performing schools while rewarding low-performing schools.39 Additionally, teachers may misinterpret behavior, erroneously rely on first impressions, or incorrectly equate their opinion of a student with the student’s social-emotional skills.40 An analysis of CORE’s survey data, however, found that the 2015 field test results were not only strongly reliable but also consistent within and between schools.41 In coming to this conclusion, the study tested for evidence of reference bias. The analysis found that students in higher-performing schools did not rate themselves more critically, which would be expected if social context influenced student responses.42 In addition, data from CORE’s 2014 pilot test suggest that teachers’ responses overlap with students’ ratings but also offer distinct perspectives. Surveying teachers, accordingly, may improve the accuracy by which schools identify students’ social and emotional skills.43 Despite this promising research, there is little to no research on how using social and emotional learning as an indicator in school classification systems would affect its validity. If CORE receives a research pilot waiver for its school classification system, students’ social-emotional skills will make up 8 percent of a school’s rating.44 This figure may be modest, but it could create real incentives to game the system and motivate students and teachers to fake survey answers in order to inflate scores. Teachers, for example, could adjust their impressions of students’ skills or coach students’ survey responses, both of which could be difficult to identify. CORE and its partners share these concerns and will continue to monitor students’ self-reported social and emotional skills. If scores significantly increase when attached to low stakes, policymakers must re-evaluate this work.45 Another way to measure students’ social-emotional skills is with performance tasks, which avoid many of the biases that threaten the validity of questionnaires. However, performance tasks also have their share of limitations. For example, practice and familiarity with tasks undermine reliability. Tasks are also extremely sensitive to administration and create random error despite efforts to control the environment. To minimize these drawbacks, schools could conceivably create numerous performance tasks that aggregate into a single score. Such an approach, however, could require an unsavory amount of testing time.46 To date, few performance assessments for social and emotional learning have been piloted at scale, and policymakers need more research to determine whether emerging tasks will be valid and reliable measures.47 SEL should inform states’ broader systems of accountabilityStates should |

| 主题 | Education, K-12 |

| URL | https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-k-12/reports/2016/12/08/294325/innovation-in-accountability/ |

| 来源智库 | Center for American Progress (United States) |

| 资源类型 | 智库出版物 |

| 条目标识符 | http://119.78.100.153/handle/2XGU8XDN/436451 |

| 推荐引用方式 GB/T 7714 | Samantha Batel,Scott Sargrad,Laura Jimenez. Innovation in Accountability. 2016. |

| 条目包含的文件 | 条目无相关文件。 | |||||

除非特别说明,本系统中所有内容都受版权保护,并保留所有权利。